With its 1948-1954 Step-Down series, Hudson introduced a truly different car to the postwar American automotive scene. Here’s more on these distinctive and fascinating vehicles.

In December of 1947 at the Masonic Temple in Detroit, Hudson introduced its all-new Step-Down series, beating Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler to the punch with an all-new postwar automobile. Radical for its time and incorporating a number of advanced features, the Step-Down Hudson has made a lasting impression to this day. This is by no means a complete history of the 1948-1954 Hudsons, simply a look at some of the more fascinating details.

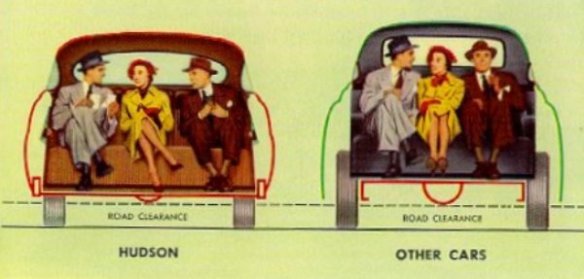

In another radical departure, the frame rails passed outboard of the rear wheels, as also shown above. This produced a tanklike structure capable of absorbing a tremendous pounding, as NASCAR racers would discover. The unusual chassis configuration also created an extremely wide rear seat, widest in the industry, but at the cost of a narrow trunk compartment, and it didn’t readily support a station wagon body style. In seven model years, Hudson never offered a production Step-Down wagon—an unfortunate gap in the lineup with the rapid growth of suburbia.

The use of unit construction also effectively took the Step-Down platform out of the light truck market, where Hudson had traditionally enjoyed modest but significant sales. But the most serious drawback of the Monobilt design was that annual model changes were limited to minor facelifts, since many of the body’s exterior hard points were baked in. This would prove critical as the Step-Down’s production cycle was extended into the early 1950s.

This Hudson illustration above shows a key feature of the Monobilt’s Step-Down design: the floor pan was not fixed on top of the frame rails but to the bottom of the structure. Passengers stepped down into the cabin, simultaneously increasing headroom and lowering the roof height. At just over 60 inches, the ’48 Hudson was four to seven inches lower than its Buick, Chrysler and Packard competitors.

This Hudson illustration above shows a key feature of the Monobilt’s Step-Down design: the floor pan was not fixed on top of the frame rails but to the bottom of the structure. Passengers stepped down into the cabin, simultaneously increasing headroom and lowering the roof height. At just over 60 inches, the ’48 Hudson was four to seven inches lower than its Buick, Chrysler and Packard competitors.

Compared to everything else on the road in ’48, the Hudson Step-Down was low, sleek, and modern, with trendy bathtub styling created by Art Kibiger under design chief Frank Spring. General Motors’ Cadillac division obtained several Step-Down models for competitive analysis, but determined that the Monobilt construction method was too complicated and costly for its purposes (see Cadillac evaluating the Hudson in this video).

In reducing the overall height, the Step-Down design also dramatically lowered the Hudson’s center of gravity, improving grip and handling. In the pages of Mechanix Illustrated magazine, America’s leading auto writer Tom McCahill raved, “This is America’s best road car by far.” NASCAR racers were also quick to exploit the Step-Down’s superior handling on the paved ovals and rough, rutted dirt bullrings of the South.

Hudson offered a variety of six and eight-cylinder inline L-head engines over the Step-Down’s seven production years, but the most famous of the bunch was the H-145 Hornet six introduced in 1951. Based on a high-chromium alloy block, the Hornet displaced 308 cubic inches—relatively enormous for a straight six at the time—and was offered in standard 145 hp form and in optional Twin-H tune with twin Carter WA-1 carburetors and an initial rating of 160 hp.

Hudson offered a variety of six and eight-cylinder inline L-head engines over the Step-Down’s seven production years, but the most famous of the bunch was the H-145 Hornet six introduced in 1951. Based on a high-chromium alloy block, the Hornet displaced 308 cubic inches—relatively enormous for a straight six at the time—and was offered in standard 145 hp form and in optional Twin-H tune with twin Carter WA-1 carburetors and an initial rating of 160 hp.

With the optional twin carbs, the big Hornet six could nearly hold its own against the latest overhead-valve V8s from GM and Chrysler. And once again, NASCAR racers were quick to seize upon the potential of the Hudson package, especially with the special 7-X high-performance components the factory quietly made available to the stock car racing crowd.

With their stiff, tough chassis, superb handling, and muscular engines, Hudsons were the sensation of the stock car circuits in the early ’50s. The Fabulous Hudson Hornets, as they were known, were the dominant brand in NASCAR and elsewhere in these years, driven by Marshall Teague, Tim Flock, Frank Mundy, and others. But arguably the most dominant performance was turned in by Herb Thomas and his crew chief Smokey Yunick (above). They went on a two-year tear in 1953-1954, winning 24 of the 71 races they entered and cementing Smokey’s reputation as one of the sharpest minds in racing.

With their stiff, tough chassis, superb handling, and muscular engines, Hudsons were the sensation of the stock car circuits in the early ’50s. The Fabulous Hudson Hornets, as they were known, were the dominant brand in NASCAR and elsewhere in these years, driven by Marshall Teague, Tim Flock, Frank Mundy, and others. But arguably the most dominant performance was turned in by Herb Thomas and his crew chief Smokey Yunick (above). They went on a two-year tear in 1953-1954, winning 24 of the 71 races they entered and cementing Smokey’s reputation as one of the sharpest minds in racing.

As the Step-Down’s production was extended into the early ’50s, the once-advanced design became dated, and sales declined from the series-high mark of 151,000 units in 1949 to 80,000 units in 1952—and kept falling from there. For 1954, Hudson designers did what they could to raise and square off the fender lines in an attempt to disguise the formerly stylish bathtub styling, but with little response from car buyers.

As the Step-Down’s production was extended into the early ’50s, the once-advanced design became dated, and sales declined from the series-high mark of 151,000 units in 1949 to 80,000 units in 1952—and kept falling from there. For 1954, Hudson designers did what they could to raise and square off the fender lines in an attempt to disguise the formerly stylish bathtub styling, but with little response from car buyers.

The Step-Down Monobilt platform was in need of a complete redesign and retooling, which the company could no longer afford due its rapidly deteriorating state. (Among other missteps, the company had invested heavily in a compact Jet model that failed to sell.) In March of 1954, Hudson reported a loss of more than $10 million in 1953 compared to an $8 million net profit the year before, and on May 5, 1954, Hudson was merged with Nash-Kelvinator to form American Motors. There were cars in the Hudson showrooms in 1955-1957, but in truth they were reskinned and rebadged Nash models. The last car bearing the Hudson name rolled off the line on June 25, 1957.